A horse isn’t born with a handbook of how to be ridden, handled, or shown.

Beyond basic instincts to eat, drink, and run away from danger, horses don’t come knowing much about what a dressage test is or that they should go over a jump instead of around it. Humans have to teach domesticated horses virtually every skill we expect them to master. I have trained several young horses, and I’ve also brought along all of my upper level horses from the beginning of their careers. I enjoy the idea that a horse can absolutely not be able to do an assigned task at one point in time (say, jump a 1.20m course) and six months or a year later be able to do so with poise and confidence. There is something about this march of progress (which of course can sometimes become a standstill or even go backwards if things go awry) that is so rewarding with a horse.

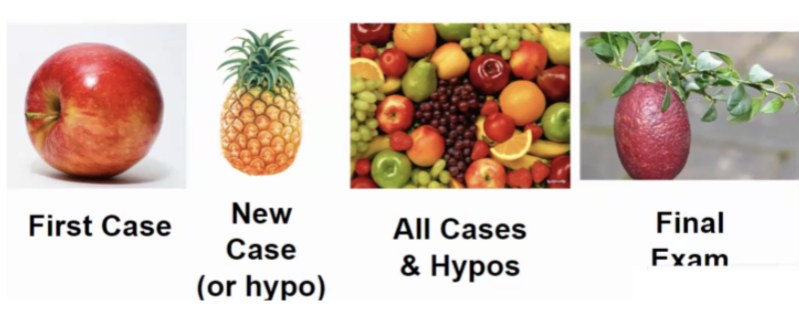

The stages of fruit salad. Photo by Ema Klugman.

The stages of fruit salad. Photo by Ema Klugman.

A member of my incoming law school class sent me some notes from a webinar the school hosted for first-year students. Since we are unfamiliar with the process and expectations of law school, the professor who was lecturing gave an analogy shown in the picture above. The picture describes the progression of our knowledge and skills in a law school class. The first case we receive in class is like an apple, which we can analyze and become familiar with. The second new or hypothetical case will look like a pineapple, but we should be able to deduce the appropriate conclusions by using our knowledge from the case of the apple. The third step will be to consider all the cases and hypothetical scenarios, which will feel like being thrown into a fruit salad—there will be some apples and pineapples, but also tons of fruit that we have never seen before. And just when we think we’ve seen everything there is to see, and analyzed every corner of that fruit salad, we will enter the final exam and find a fruit we didn’t even know existed. It looks to me like a passion fruit, but really it could be anything. To ace the final exam, we have to be resourceful and creative with our analysis.

Training a horse means getting them from the apple stage to the passion fruit stage—by way of the pineapple and fruit salad stages.

Let’s take, for example, teaching a horse to jump. The apple is a cross-rail. The pineapple is the horse’s first vertical and oxer, perhaps with some fillers thrown in. The fruit salad is a course of jumps: some verticals, some oxers, maybe even some logs and combinations. The passion fruit, or final exam, is all of these things at a horse show, with horses screaming, flags waving, wind blustering, and a warm up area teaming with other horses. A horse who passes the final exam will have gained confidence from each step: cross-rail to verticals and oxers, verticals and oxers to courses, and courses to horse shows with distractions and spookier courses. If you skip one of the intermediary steps, you’re unlikely to pass the final exam.

There may be a little passion fruit in this fruit salad… Photo by Engin Akyurt/Unsplash/CC.

There may be a little passion fruit in this fruit salad… Photo by Engin Akyurt/Unsplash/CC.

Perhaps it is a strange analogy, but anyone who has trained young horses will understand how incremental a process it really is. In no world would someone take a horse to a show to jump a full course after it had only jumped a cross-rail or two. The horse has to see things in training so he is familiar with them when he arrives at the show, even if they look like a fruit salad in disguise. The analogy works for all sorts of training: flatwork, jumping, cross country, groundwork, even teaching the horse how to load on a trailer. The main idea is that the horse gains security from familiarity, which is why proceeding in incremental steps is so important.

Eventers and jumpers will especially know this incrementalism to be crucial.

Progressing up the levels, one feels the horse understand new questions because previous courses have presented them in smaller and simpler ways. For instance, a training level eventing course will have preliminary-type jumps, but they will be at 1.0m instead of 1.10m, and be slightly less technical. This progression allows the horse to become familiar with certain questions. One of my young horses did not exactly take to cross country like a fish to water. She was spooky, dramatic, and distracted by spectators for her first few events. She didn’t really recognize the fruit salad, so to speak, although we had done plenty of practicing and exposure. About a year into her eventing career, she seemed to really “get it” and become familiar with the sport, especially the cross country phase. Each time I moved up a level, she was able to recognize the new questions as simply variations on the previous ones. Now she hunts down the jumps like a sniper.

It can be enormously frustrating to arrive at a show feeling prepared and have a young horse be surprised or just too green for the tasks presented. A horse schooling 1.20m at home may feel green and confused at a show when asked to jump a 1.10m course. Instead of calling them naughty or deducing that they are not brave, we should remember that the step from fruit salad to passion fruit—from the comprehensive study guide to the final exam—is actually quite a big one. Exposing your horse to all the types of fruit you can in training will help prepare her for competition, but at some point she will face something unfamiliar and have to figure it out for herself. Let your horse do that; let them think. You will have an amazing partner on the other side of it.