Earlier this month, we launched a $5,000 Diversity Scholarship with the support of generous donors, inviting minority equestrians to contribute to the discussion of diversity and inclusion in equestrian sport.

It is the mission of this annual bursary, which we intend to expand in coming years, to call for, encourage, elevate and give a platform to minority voices in a space where they are underrepresented.

We received 27 submissions representing a broad spectrum of gender, racial, ethnic, sexual and class identities. They are eventers, hunter/jumpers, dressage riders, polo players, western riders, and more. There is no way to “judge” or “rank” them, as each voice is important and limitless in its own value. In lieu of declaring a winner, we have expanded the fund to award each applicant $200. Whether it’s put toward lessons or a show entry or a needed item of tack/rider gear, the fund is intended as a tangible gesture of support and a small contribution toward change with much more work still to be done in the future.

How do we build a more diverse, inclusive and accessible sport? In the coming weeks we will explore this question alongside many of the Scholarship recipients as they share with us their essays in full.

We urge you to sit with them, and truly listen with an open mind and heart. Caden Barrera advises, “Take your hands off the keyboard. Take a breath and wait. Stop drowning out qualms of oppressed peoples. Let them, let us have the microphone for a second. Hear what we have to say.”

And we hope that hearing these voices will spur you to take action. The time for a radical redress of our sport is long past due, and it’s going to take a community-wide commitment and follow-through to create real structural change. To help facilitate this, Nation Media will be collating the essayists’ actionable ideas and connecting them with the public as well as leaders and stakeholders of the sport. “This is a catalytic moment within our community,” says Malachi Hinton.

A heartfelt thank you to all 27 Scholarship recipients who have contributed to this important discussion.

Collectively, their perspectives, insights and ideas coalesce into a body of work that will no doubt help inform a viable path forward for equestrian sport. We’ve patchwork-quilted together some highlights from their essays below with much more to come.

To all minority equestrians, please know that you always have a seat at the table here.

Dawn Edgerton-Cameron. Photo by Rough Coat Photography.

Dawn Edgerton-Cameron. Photo by Rough Coat Photography.

“Why is there such a lack of diversity in horse sports, and how do we foster more inclusion?”

Dawn Edgerton-Cameron begins with this question, for which which there is no easy answer. “Like most complicated issues, there are many reasons, which means there’s no one path to resolution and correcting it requires a multifaceted approach.” In her opinion, the key factors are exposure, opportunity, perception, and reception.”Each in itself is a multi-layered issue but also overlaps with the others, making it an even thornier issue to untangle.” Dawn lists some ways we can help in the areas of marketing and support/allyship. “If each of us commits to taking just one or two of the above actions,” she concludes, “we can get there a lot faster.”

Photo courtesy Anastasia Curwood.

Photo courtesy Anastasia Curwood.

Anastasia Curwood points out how Jim Crow racism largely erased the rich history of Black equestrianism: “Americans quickly forgot that the foundations of the tremendously popular sport were in Black talent. By the time I was putting a leg over a school pony almost 100 years later, it seemed like horses had always been for white people only.” Now, she says, she knows better and is proud to be a Black equestrian who is looking to resurrect the historical memory of my forebears via the Chronicle of African Americans in the Horse Industry project. “We need to change the idea that horse sports are not for Black people.”

Photo courtesy Lea Jih-Vieira.

Photo courtesy Lea Jih-Vieira.

Lea Jih-Vieira explores the relationship between race and vestigial socio-economic issues have made horses an impossible dream for many. “The historic systems in place, meant to limit people of color, are so interwoven in the fabric of our country that we may not even realize how much they influence our lives today,” she writes. “If we fail to acknowledge just how many barriers are inherent to the sport, we fail to make it accessible to all.”

Katherine Un lists out those barriers, including but not limited to access to land, financing and education. “Our histories of disempowerment mean that young minority equestrians do not have the generational wealth and social capital of our white counterparts.” She reminds us that that equestrian sport does not exist in a bubble nor should our efforts be self contained: “In parallel to diversity and inclusion work in our equestrian community, I would strongly encourage all horse-people to support anti-racist efforts outside the horse world.”

The problem runs deeper than socioeconomics, adds Caden Barrera. “Our discussion on inclusivity and equality needs to begin shifting to more personal critiques — of ourselves and of others who may not be making our spaces safe and accepting. I want to see the conversations about economic status and politics equally matched by conversations about how our local barns can do better, how we can start unlearning bias, how we can make changes.”

Racism, as well as homophobia and elitism, manifest in myriad ways. Julie Upshur writes that the racism she has experienced as a rider would mainly be classified as micro-aggressions, perhaps even out of ignorance, like being asked how she fits her hair under her helmet. Once, a white woman said to her that she was lucky to take care of such nice horses: “To her, I couldn’t possibly be anything but the help.” Scnobia Stewart talks of prejudice and discrimination disguised in witty, covert remarks: “These forms of subtle racism are extraordinarily disheartening to individuals who are just trying to have fun participating in a sport they are passionate about.” Many spoke of stares and sideways glances that seemed to say, what are you doing here?

Malachi Hinton and F15. Photo courtesy Malachi Hinton.

Malachi Hinton and F15. Photo courtesy Malachi Hinton.

Other recipients recall more opaquely discriminatory experiences. Like Malachi Hinton, who writes of how at one of her first local shows, another competitor refused to share the ring with her.

Leilani Jackson and Primo. Photo courtesy Leilani Jackson.

Leilani Jackson and Primo. Photo courtesy Leilani Jackson.

Or Leilani Marie Jackson, who was verbally and nearly physically abused while volunteering at the in-gate of a horse show.

Photo courtesy Madison Buening.

Photo courtesy Madison Buening.

And Madison Buening, who was taken advantage of, accused of lying, and denied pay while working at the barn and horse shows — “a slap in the face,” she writes. “Since then, the only being in the horse world that I have trusted is my horse.

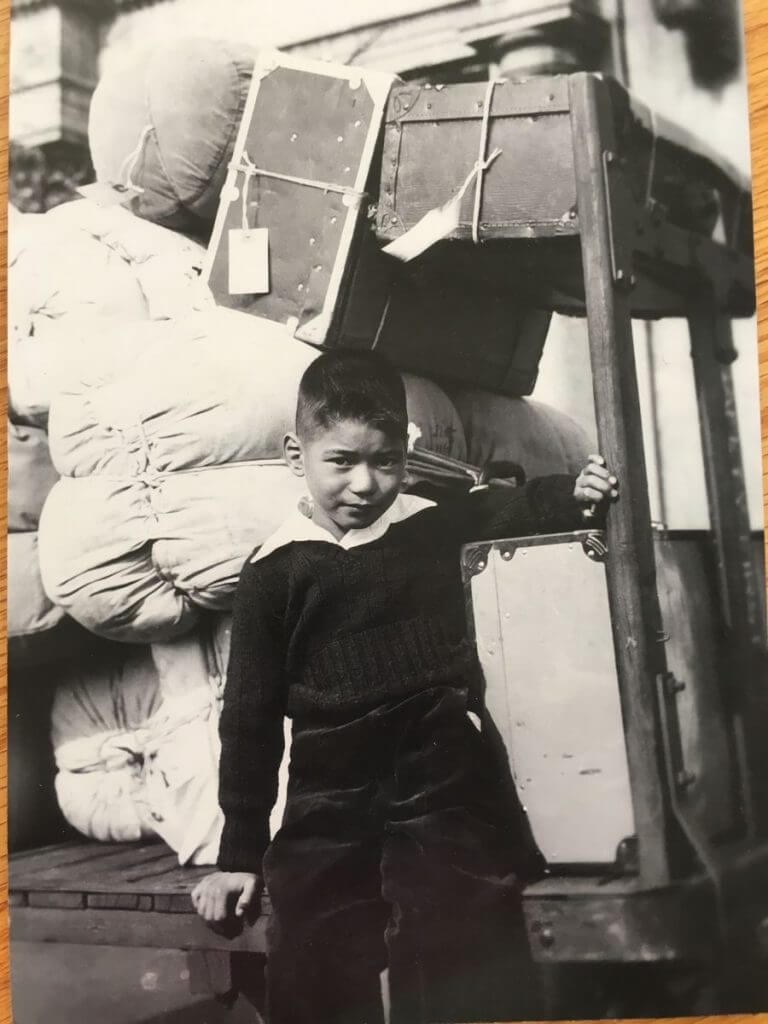

Photo courtesy Kimberly Kojima.

Photo courtesy Kimberly Kojima.

When Kimberly Kojima hears the phrase “systemic racism,” she says thinks of how as a boy her father, along with some 120,000 other Japanese Americans, were forced into internment camps. He was sent to live in a horse stall on a Salinas, California, racetrack turned internment camp, while his father was separated from their family for four years. When Kimberly’s father first put her on a horse, she said, it was an act of taking back their power.

Aki Joy Maruyama on Balou Moon. Photo by Mathieu O’Regan.

Aki Joy Maruyama on Balou Moon. Photo by Mathieu O’Regan.

All of the above factors, and more, add up to a glaring absence of diversity within the horse world.

“I have never met another Black eventer in person. Never,” says Julie Upton. “I occasionally see upper-level riders who are part of the LGBTQ community, but I have never seen any other transgender people,” says Caden Barrera. “For 28 years, I have yet to meet a single equestrian who looks like me,” reflects Dana Bivens. “This is a sobering and isolating truth, which speaks to how homogenous our sport is and how this lack of diversity limits our potential to expand audiences, grow equestrian communities, generate revenue and support, and to make the joys of riding and horses available to everyone.” It took seeing a Black eventer at Fair Hill to convince Deonte Sewell that he could be more than a racetrack groom. Aki Joy Maruyama, age 20, says, “My hope is that other minorities watching me compete feel inspired to enter the sport.”

Media representation, too, has historically focused on the images and stories of white riders. Deonte Sewell observes, “In most old Hollywood movies the farmhands/grooms were always of a minority descent. They seemed to always know more about riding and horses than the actual trainers but never portrayed the trainers or professional riders themselves. Why does it seem that the only place in the show world for minorities is to pick up after the kings and queens of the sport?” That lack of representation continues today, says Helen Casteel: “Right now when I open an equestrian magazine, I usually see nothing but pale faces. You all literally can’t see us.”

White stakeholders who are “listening,” “learning” and striving to “do better,” without doing much beyond posting a black square or a vague statement about racial justice on social media, are falling short. Lyssette Williams writes, “While #BlackOutTuesday was a resounding social media success – BIPOC riders like me are watching and waiting. It is not enough to commodify a moment in a movement – brands, publications, and organizations now need to roll-up their sleeves and buckle down for a lifetime of work building trust and equity for the BIPOC equestrian community.” While acknowledging that minority riders should not have to shoulder the brunt of the work, she follows that up with a 2,000-word actionable list for organizations and management companies to start conversations internally.

Helen Casteel on Unapproachable. Photo by Shannon Brinkman Photography.

Helen Casteel on Unapproachable. Photo by Shannon Brinkman Photography.

Helen Casteel urges the sport’s leaders to be more proactive in expanding the sport’s reach. What if, she asks, professional riders took it upon themselves to engage area riding students, as British Olympic show jumping gold medalist Ben Maher did with the Ebony Horse Club? What if USEF leadership facilitated these new relationships and supported their growth? Like Lysette, she clarifies that the responsibility to create and implement solutions shouldn’t fall to minorities. White equestrians and stakeholders must assume accountability. “Real change will only happen when white people truly prioritize diversity and representation efforts. This has to become your problem to solve.”

Alvin Geronimo Markey. Photo courtesy Frank Markey.

Alvin Geronimo Markey. Photo courtesy Frank Markey.

Historically, young people have been drivers of social change, as we’ve seen in recent months with the Black Lives Matter movement. Within the equestrian community we have been encouraged to see activism from young equestrians, who are thinking outside the box for creative, effective solutions. Morgan Fenrick, the 20-year-old founder of the Queens University of Charlotte eventing team, proposes a virtual mentorship program connecting industry professionals and minorities. Katarina Stovall, age 15, would like to see a nonprofit that collects used tack from upper level riders as a donation and loans to it to riders with more limited resources. Christine Wilson, age 24, envisions a developmental program “focused on creating and maintaining diversity in our sport, similar to Young Riders programs, [that] will create opportunities for minority riders to access a network of mentorship, sponsorship, and funding. This program will be a safe and inclusive space for those that have historically felt unwelcomed in the sport by providing access to resources which will level the playing field for minority equestrians to pursue their goals.”

Photo courtesy Briannah McGee.

Photo courtesy Briannah McGee.

In spite of troubling narratives we noticed a pervasive thread of optimism throughout the essays, a shared belief in the power of horses to unite rather than divide us. Briannah McGee, age 15, writes, “When we ride together, our ethnicities, sexuality, cultures, or any other differences do not define us,” noting that horses can also break down barriers for people with mental health issues or physical disabilities. At its best, the equestrian community can be a safe space of acceptance and welcoming. Muhammad Shahroze Rehman recalls his anxiety at his first University of Florida equestrian club meeting, being both a minority and a male in a room full of more than 100 females. “I became nervous and took a seat in the farthest corner,” he says. “My anxiety and nervousness went away when my team captain approached me and said, ‘Hey Muhammad, why don’t you come to sit with the Eventing team.’”

Many of the essays also brim with pride. Christopher Ferralez says, “Minorities can be a positive and powerful voice in our community … I find that being Latino is a very valuable asset. I am fluent in both English and Spanish, and I feel that I am more relatable and personable to some of our industry’s amazing staff that only speak Spanish.” An affirmation from Jen Spencer: “Diversity in equestrian sport is small, but it’s there and it’s strong.”

Kaylawna Smith-Cook on Passepartout. Photo by Shannon Brinkman Photography.

Kaylawna Smith-Cook on Passepartout. Photo by Shannon Brinkman Photography.

Collectively and as individuals, it is our responsibility to create a more diverse, inclusive and accessible sport. The work has already begun and there is a place for us all in the effort. “This will not be easy,” says Lyssette Williams. “It is an uphill climb that will require everyone who cares for the longevity of equestrian sports to do the work. The love we have for horses should be what brings us together and raise us up, not tear us apart.”

To conclude, a call to action from Kaylawna Smith-Cook: “Now is the time for us to develop a better future so that our children and loved ones may live in a world free of racism and discrimination, one where they can truly be judged by the content of their character and not by the color of their skin.”

Nation Media wishes to thank Barry and Christine Oliff, Katherine Coleman, and Hannah Hawkins for their generous financial support of this Scholarship. We also wish to thank our readers for their support, both of this endeavor and in advance for all the important work still to come.