This excerpt from Sport Horse Conformation by Christian Schacht is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (www.horseandriderbooks.com).

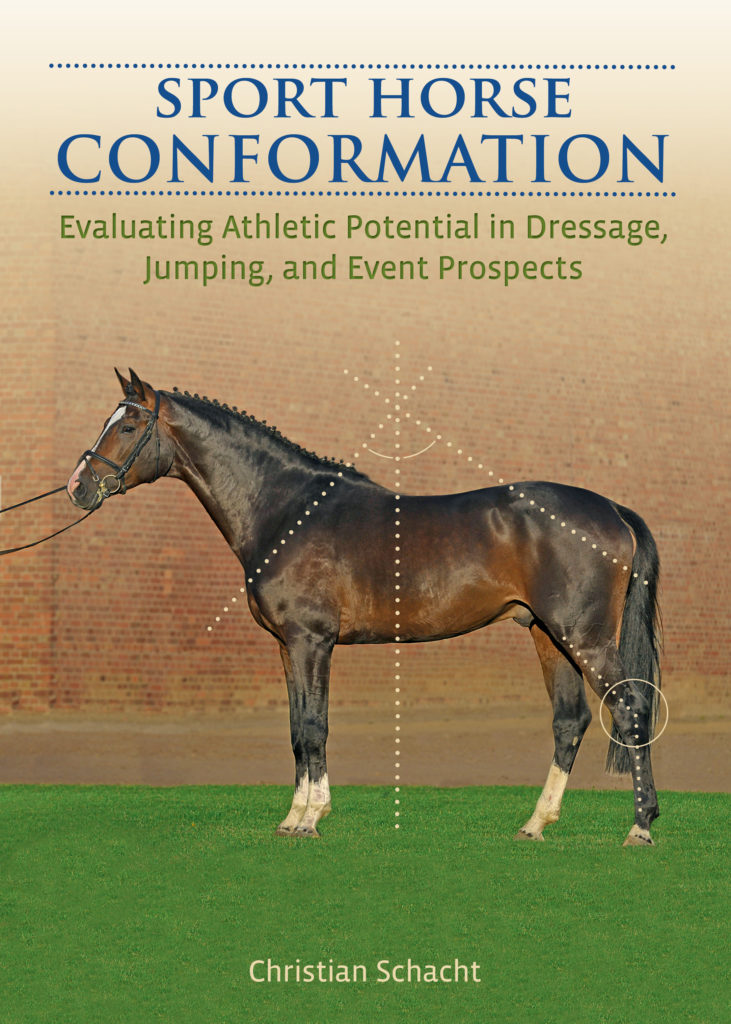

In this excerpt from Sport Horse Conformation by veterinarian and German FN-certified breeding and horse management expert Christian Schacht, find out what to look for in a jumper prospect when it comes to front-end conformation.

The position and angle of the horse’s shoulder allow you to notice potential, even in the newborn foal. The shoulder has a significant effect on the forelegs’ ability to cover ground, which, in turn, determines the use and the basic quality of the horse.

The shoulder plays an important part in the evaluation of the overall quality of the horse. The shoulder’s length should just about equal the distance from the poll to the indentation in front of the withers. The shoulder should never be shorter than the head. Its angle to the ground should be parallel to the angle of a normal pastern. The connection of the shoulder to the horse’s upper forelimb (scapula to humerus) should form a right angle or, even better, less than 90 degrees.

When the point of shoulder to topline angle is more upright (straight), the shoulder-to-upper-forelimb angle will be more than 90 degrees, and quality of movement is affected.

When a forward-set shoulder (meaning the line from the point of the shoulder up the scapula ends in front of the withers) has a 90-degree or less shoulder/upper forelimb angle, it can be somewhat advantageous for a jumper.

A decisive factor for quality of movement is the length of the shoulder. A long, more angled shoulder works like a pendulum and not only provides better shock absorption but also increases length of stride in all gaits; as the pendulum’s trajectory decreases, the angle to the upper forelimb remains the same and the entire leg is positioned too far back. This causes rushed, rather limited movement in all gaits.

The pivot (rotation) point determines the effect of the above-mentioned pendulum. The pivot point is most easily seen when a horse is in motion. During the walk, for example, you can see a part that is going backward and another that is going forward. Exactly between these parts is the pivot point. The higher it is on the shoulder, the more freedom the horse will have in the shoulder. The minimum requirement is that this point has to be, at the very least, the same height as the hip joint.

On an ideal “dressage” shoulder, you can draw a line from the point of the shoulder, up over the spina scapulae (an easily palpable bony ridge), to the middle of the withers. In this position, the shoulder—in combination with an ideally long upper forelimb (humerus)—enables optimal forward range of motion and an ability to cover ground. Even though the quality of an extended trot depends on the engagement of the hindquarters, the length of stride of the front limbs demonstrates the expression of a spectacular gait.

In the case of a show jumper, however, the above-described ideal “dressage” shoulder may stand in the way of success. It is preferable that the shoulder for a show jumper is set a little bit more “forward”—the line drawn up from the point of the shoulder over the spina scapulae ends a bit in front of, or at least in the front area of the withers). Horses with such a shoulder have a slightly more limited gait quality. Therefore, they have an even greater need for development of the carrying and “spring” power of the hind legs in order to minimize the horse’s tendency to support himself on the front legs. However, horses with such conformation can show nearly lightning-fast reflexes above a jump. Leg technique has become quite popular (high marks gained in young horse jumper tests in Europe); nevertheless, a horse that “jumps through the body” and “opens behind” is always preferable to a horse with faster front limbs.

In contrast to the pelvic limbs, the shoulder has no bony attachment to the trunk of the horse. Ligaments, muscles, and fasciae all together form a sort of net in which the horse’s trunk is suspended between the front limbs. This protects the body from the wear caused by strain from constant grazing. At the same time, the shoulder acts as a shock absorber—during drop jumps or similar movements—in order to prevent torn muscles or injuries to tendons and ligaments. This shock-absorber function is achieved when the shoulder angle equals the angle of the side of the hoof (and pastern). Ideally, both angles should be about 45 to 50 degrees.

You can snag your copy of Sport Horse Conformation from Trafalgar Square Books HERE!